Larisa is a flawed human. Also, an anthropologist, an independent scholar, and a beekeeper. Her latest book, Beekeeping in the End Times (2024) and the documentary film by the same title, concern Islamic eco-eschatology, honeybees, and climate change. Lately, she’s been investigating robobees and ecologies of inspiration. With her best friends, Larisa’s been writing the Children of Salik : a series of children’s climate fiction books. She used to love teaching at the University of Chicago and appreciated the spell of time she spent at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin.

You can reach Larisa at jasarevic.g.larisa@gmail.com

You can reach Larisa at jasarevic.g.larisa@gmail.com

Azra is an independent filmmaker. A graduate of the International School for Film and Television, San Antonio de los Baños, Azra has been filming worker struggles and social justice movements in the context of post-socialist economic and environmental crises.

Zumra, an economist by training and a long-time writer, is now retired as a fulltime gardener. Also, a bee-lover. The most practically-minded one in the family, she has the final word in the household and keeps our apiary’s records and our expense log. The business of our beekeeping to date, according to her count, is financially reckless. But the joy remains non-countable and the honey we do manage to harves, is the sweetest.

Azra had a great time working working for the local radio and television station, RTV-7, based in Tuzla, northeastern Bosnia. Currently, she runs a film and multimedia school for young adults in Tuzla and works in acquisitions for Taskovski Films. With her sister, Larisa, Azra is currently post-producing the documentary Beekeeping in the End Times and researching for their next film project entitled Arboreal Cinema. You can reach Azra at azrajasarevic10@gmail.com

Pepe is ever being a cat.

Postcards from our village and apiary

These days, we keep bees, grow food, and otherwise film, write, and work in a mountaintop village in northeastern Bosnia. It’s a steep patch of a funnel-shaped land we inherited from our father, along with an unruly orchard whose edges are furrowed by a creeping landslide. We are now a matriarchy; our mother is to our land what a queen bee is to a hive.

Winter 2025

A storm on the outside. Within, devoted insects are unsleeping, keeping the heart of their world warm.

Fall 2024

Heirlooms

Heirlooms

Summer 2024

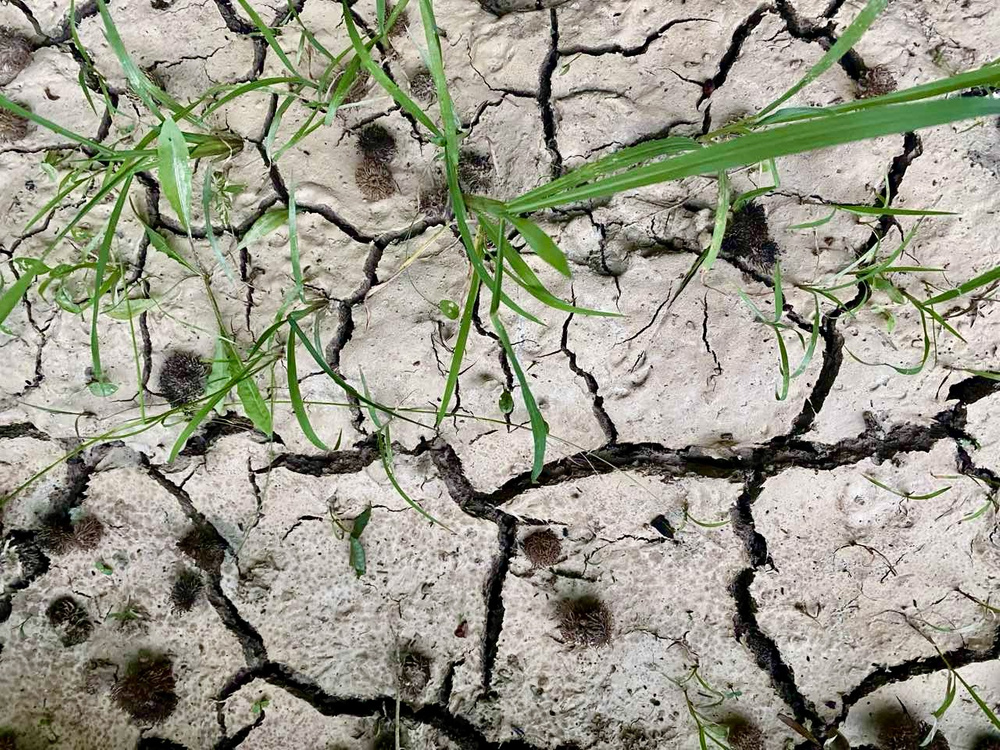

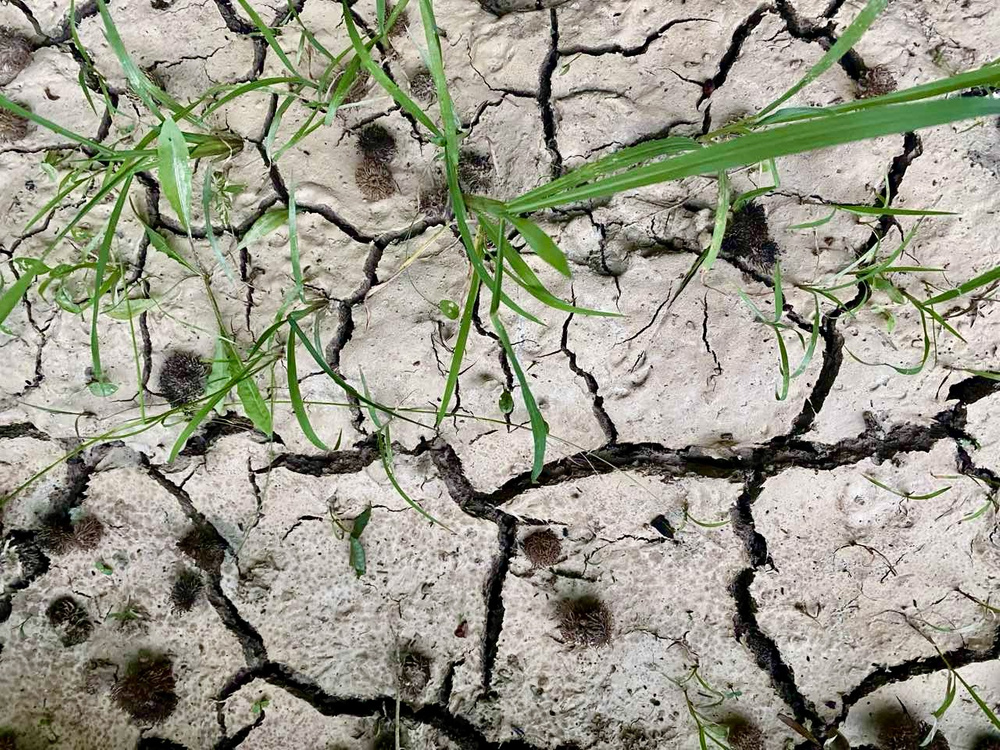

July 2024. Hot as hell, our summer. Frogspawn used to linger and dragonflies once droned on this patch of the road on the way to the forest .

Spring 2024

March 29th dawned brilliant and unseasonally warm. We took a long walk through the fields and forests. Mom and Azra hunted the forest for bear’s garlic while I stalked the foraging bees. There was not much for the bees to find in bloom besides dead nettles, primroses, and wild violets. And this strange forest flower—can anyone name it? Raw and pink as flesh, the flowers emerge beneath the blanket of last year’s leaves, as if they were shrouds. Arching low above the ground, the florets are hiding, though not from the bees.

Sometime in late May, 2021. A plunge: deep within the parted petals is an offering. We name it pollen but who could tell what the treasure means to this bee.

Sometime in late May, 2021. A plunge: deep within the parted petals is an offering. We name it pollen but who could tell what the treasure means to this bee.

Blooms came out way too early. But they are as gorgoues as ever.

Spring 2020

The many honeybees that live on our land occupy seventeen hives (among them is a wicker skep!). Our apiary is truly small but our greatest feat is that we’ve been managing to keep the bees alive and healthy over the years. We have harvested honey only three times, since 2015. Gorgeous, umber-colored linden, mixed in with black locust and blackberry blossoms, the honey is so fragrant that a whiff alone gives you a buzz. The jars warm up with golden hues as the honey crystalizes. All other years, we have fed honey and pollen (bought from a trusted source) back to the bees.

Without this emergency food aid (a snapshot of its production above), our bees would not have fared well through the dearths due to strange weather. As the signs of global climate change become more immediately felt on the ground--even ground such as ours, far from industrial pollution and industrial agriculture, lovingly cultivated with bee-friendly flora and surrounded by forests and wilds--it is not clear how much longer we will be able to keep bees. In the meantime, with their perseverance, their beauty, their buzzing that sounds like invocation to Sufis and, anyhow, feels like a blessing, their swarming, nectar gathering, pollen foraging, pollinating and other acts of faith under inclement skies, the bees are keeping us going.

These days, we keep bees, grow food, and otherwise film, write, and work in a mountaintop village in northeastern Bosnia. It’s a steep patch of a funnel-shaped land we inherited from our father, along with an unruly orchard whose edges are furrowed by a creeping landslide. We are now a matriarchy; our mother is to our land what a queen bee is to a hive.

Winter 2025

A storm on the outside. Within, devoted insects are unsleeping, keeping the heart of their world warm.

Fall 2024

Summer 2024

July 2024. Hot as hell, our summer. Frogspawn used to linger and dragonflies once droned on this patch of the road on the way to the forest .

Spring 2024

March 29th dawned brilliant and unseasonally warm. We took a long walk through the fields and forests. Mom and Azra hunted the forest for bear’s garlic while I stalked the foraging bees. There was not much for the bees to find in bloom besides dead nettles, primroses, and wild violets. And this strange forest flower—can anyone name it? Raw and pink as flesh, the flowers emerge beneath the blanket of last year’s leaves, as if they were shrouds. Arching low above the ground, the florets are hiding, though not from the bees.

Blooms came out way too early. But they are as gorgoues as ever.

Spring 2020

The many honeybees that live on our land occupy seventeen hives (among them is a wicker skep!). Our apiary is truly small but our greatest feat is that we’ve been managing to keep the bees alive and healthy over the years. We have harvested honey only three times, since 2015. Gorgeous, umber-colored linden, mixed in with black locust and blackberry blossoms, the honey is so fragrant that a whiff alone gives you a buzz. The jars warm up with golden hues as the honey crystalizes. All other years, we have fed honey and pollen (bought from a trusted source) back to the bees.

Without this emergency food aid (a snapshot of its production above), our bees would not have fared well through the dearths due to strange weather. As the signs of global climate change become more immediately felt on the ground--even ground such as ours, far from industrial pollution and industrial agriculture, lovingly cultivated with bee-friendly flora and surrounded by forests and wilds--it is not clear how much longer we will be able to keep bees. In the meantime, with their perseverance, their beauty, their buzzing that sounds like invocation to Sufis and, anyhow, feels like a blessing, their swarming, nectar gathering, pollen foraging, pollinating and other acts of faith under inclement skies, the bees are keeping us going.